28. Did humans settle New Zealand before the Polynesians?

- Kerry Paul

- Jun 1, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Dec 21, 2025

The Possibility of Pre-Polynesian Settlement in New Zealand

The previous Blogs have explored this question. Now is the time to weigh up the strength of the evidence to reach a view on the subject: Who were New Zealand's first settlers?

Introduction

The prevailing academic consensus holds that New Zealand was first settled by East Polynesians around 1280 AD. However, an alternative theory proposes that New Zealand may have been inhabited by earlier peoples—possibly arriving over 2000 years ago—from Southeast Asia, Melanesia, or beyond. The blog "First Settlers in New Zealand" presents a comprehensive, multifaceted argument in favour of this theory, drawing upon archaeological, oral, linguistic, navigational, and genetic evidence. This Blog evaluates which of these strands provides the strongest evidence for pre-Polynesian settlement.

The Strongest Case: Archaeological Evidence from Poukawa Excavation

Of all the lines of inquiry presented, the archaeological findings at Poukawa, Hawke's Bay, provide the most single compelling evidence supporting the claim of human presence in New Zealand prior to 1280 AD.

Key Findings:

In 1962, surveyor Richard Price and soil scientist Allan Pullar uncovered moa bones and stone tools beneath two distinct volcanic ash layers, the upper from the Taupo eruption (186 AD) and the lower from the Waimihia eruption (~1400 BC).

The artefacts were sealed beneath these layers, which traditionally implies they pre-date the volcanic events, particularly if stratigraphy is intact.

Charcoal and pollen samples collected supported the conclusion of a human presence in the area as early as 1400 BC, placing it well over 2000 years before the Polynesian arrival.

The stone tools found included materials not local to the region (e.g., red quartz), suggesting either trade or migration.

Supporting Arguments:

The complete extinction of all moa species by ~1440 AD suggests prolonged human exploitation. Given the small size of the initial Polynesian settler population, their impact alone seems insufficient to explain such rapid extinction unless earlier hunting pressures existed.

Similar stratigraphic evidence elsewhere (e.g., Bruce Bay adzes found under 5–6m of soil) may point to significant soil accumulation timelines, reinforcing claims of ancient occupation.

The Case For: Other Supporting Evidence

While the Poukawa excavation is pivotal, it is reinforced by other circumstantial but significant evidence:

1. Māori Oral Traditions

Numerous 19th-century European observers, fluent in Te Reo, recorded Māori oral traditions of earlier peoples—e.g., the Waitaha, Patupaiarehe, and Ngatimaimai—described as small, dark-skinned, or fair-skinned and peaceful.

Reports by respected figures like Andreas Reischek, J.S. Polack, and John Macmillan Brown lend credibility to these traditions.

Ngāi Tahu acknowledge the Waitaha as the first people of the South Island, even predating Ngāti Māmoe and Ngāi Tahu themselves.

2. Other Archaeological Anomalies

Stone structures in Waipoua Forest, extending over hundreds of hectares, suggest intensive, multi-generational occupation and complex social organization.

Selection of Stone Structures in the Waipoua Forest

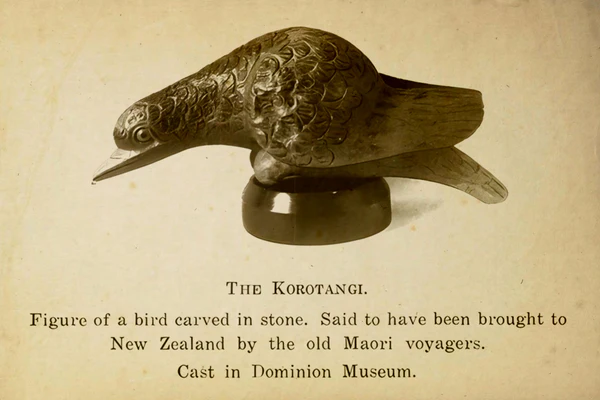

Carved artefacts (e.g., the Pouto Panel, Korotangi bird, and Tamil Bell) imply contact with or origin from South Asia or Southeast Asia, predating known European arrival.

The Carved Stone Bird (Korotangi Bird), Pouto Panel and Tamil Bell

The Weka Pass rock art, investigated by Julius von Haast, depicts animals not native to New Zealand and resembles South Indian iconography.

3. Genetic and Linguistic Evidence

Y-chromosome data show significant Melanesian and some European influence; mtDNA indicates a maternal lineage from Southeast Asia.

Edward Tregear's comparative linguistics demonstrated remarkable parallels between Māori and Sanskrit, suggesting an older, shared linguistic ancestry possibly via Southeast Asia.

4. Oceanographic and Navigational Feasibility

The presence of the East Australian Current (EAC) and robust inter-island maritime networks supports the plausibility of accidental or intentional voyages from Southeast Asia or Melanesia.

Motivations like resource scarcity, conflict, or curiosity mirror known drivers of human migration globally.

Conclusion: Assessing the Possibility of

Pre-Polynesian Settlement in New Zealand

When evaluating the full breadth of evidence—archaeological discoveries, Maori oral traditions, linguistic patterns, genetic markers, and other anomalies—it becomes clear that the possibility of an earlier human presence in New Zealand cannot be entirely dismissed. The strongest case comes from the Poukawa excavation, where stone tools and moa bones were discovered beneath volcanic ash layers dated well before the Polynesian arrival. While some scholars question the integrity of the stratigraphy, the presence of non-local materials and supporting charcoal samples suggests genuine human activity over 2000 years ago.

Additionally, oral traditions consistently refer to earlier inhabitants, such as the Waitaha and Patupaiarehe, whose descriptions differ significantly from known Polynesian settlers. While these accounts could be mythological in nature, their widespread documentation hints at deeper ancestral memory. The existence of unusual artefacts, rock art, and stone structures further complicates the mainstream narrative, pointing to external influences or possible pre-Polynesian occupation. Genetic studies show Polynesian ancestry, yet traces of Melanesian and Southeast Asian maternal lineages provide room for speculation about intermingling with an earlier population.

While conventional scholarship maintains that Polynesians were the first settlers, the cumulative evidence—viewed holistically—suggests that the question is far from settled. Acknowledging gaps in research and the potential for new discoveries, a cautious but open-minded approach remains essential in understanding New Zealand’s deep human history.

Taking into account all the evidence presented in this blog series: Who do you think were New Zealand's first settlers? Feel free to write a comment or contact me to keep the discussion going...

Continue your reading with looking at the next series on Early European Explorers to New Zealand: 1. Did European explorers visit New Zealand before Abel Tasman in 1642AD?